As you drive east on Great Bay Boulevard in Little Egg Harbor Township, the newly rebuilt houses become fewer, painted lines on the road disappear and the view ahead becomes blue sky, marshes and open water.

After crossing several one-lane wooden bridges with a speed limit of 10 miles per hour, a compound in the distance becomes clearer. A long wooden footbridge leads to a massive white 1930s-style house with a red roof.

The Rutgers University Marine Field Station sits surrounded by tall grasses, beach and water. The structure would never be approved for this location today, but scientists and researchers are reaping the benefits of foundations laid by the U.S. Coast Guard nearly 80 years ago.

“The Coast Guard was in here into the ‘60s, but then abandoned this and other stations,” said Ken Able, a marine scientist and writer. “The university took it over in 1972 and has slowly, over the years, renovated it for research while maintaining some of the positive aspects of a Coast Guard station.”

Able is the author of “Station 119: From Lifesaving to Marine Research,” released last year. The book details the history of the station’s conversion from military uses to scientific ones and the importance of its ongoing research in marine science.

“I wrote the book for the general public, to help them understand what research means and its importance,” he said, “and in the process, to help people understand how things can change over time.”

A lot of that change has to do with the marine environment, Able said. On a recent Wednesday afternoon, he sat in his office, his desk piled with papers and maps. Amid the organized chaos was a skeleton of a fish arranged on a plaque.

Outside a window and beyond the white porch that wraps around the first floor of the building, Able can see the Jacques Cousteau National Estuary. Near the station, waters from the Mullica River flow into Great Bay and past it, into the Atlantic Ocean.

What looks like a shiny dog’s nose peaks out of the water and dips back down with the waves. Local harbor seals have been enjoying the warmer air and water temperatures of an unusually mild winter. They aren’t the only living creatures Rutgers scientists have been able to study recently.

“We’re watching the temperatures getting warmer each year,” Able said. “This year was crazy. We see that in the fishes still here, like summer flounder and fluke larvae. There’s more than we’ve ever seen.”

Temperature ranges at the Jersey Shore are some of the broadest in the world, according to Able and Thomas Grothues, an associate research professor. One of the primary research projects at the station is the study of fish and how they respond to changes in the environment over time.

When the researchers say this winter’s collections have been different than any other year, they’re talking from more than 25 years of experience.

Scientists have collected specimens from the water off the station’s long wooden walkway every day since 1989. The boardwalk is framed by telephone poles with charred, black wood. A fire in 1976 nearly destroyed the walkway and endangered the station.

Fires aren’t uncommon in the station’s history. The first recorded one was in 1955 during the Coast Guard years. Evidence of the fire can be seen in charred timbers under the house deck. The third floor, which now contains offices and marine research materials, had to be completely rebuilt after a 1969 fire caused by a lightning strike.

After Hurricane Sandy hit the coast in 2012, many wooden structures had to be rebuilt, but the main station survived unscathed — unless you count the plumbing.

“They evacuated us for Irene and Sandy, but nothing structurally was disturbed,” able said. “After Sandy, we were 1,100 days and counting that we couldn’t flush the toilets, but I’d rather be here than anywhere else.”

More than three years after Sandy, the majority of problems have been taken care of, but the station’s wet lab is still unusable. The lab is supposed to allow scientists to take marine life from the bay for observation, where they can manipulate conditions to speed up organism development.

Able said the money to fix the lab has been budgeted, but it’s tied up in bureaucracy.

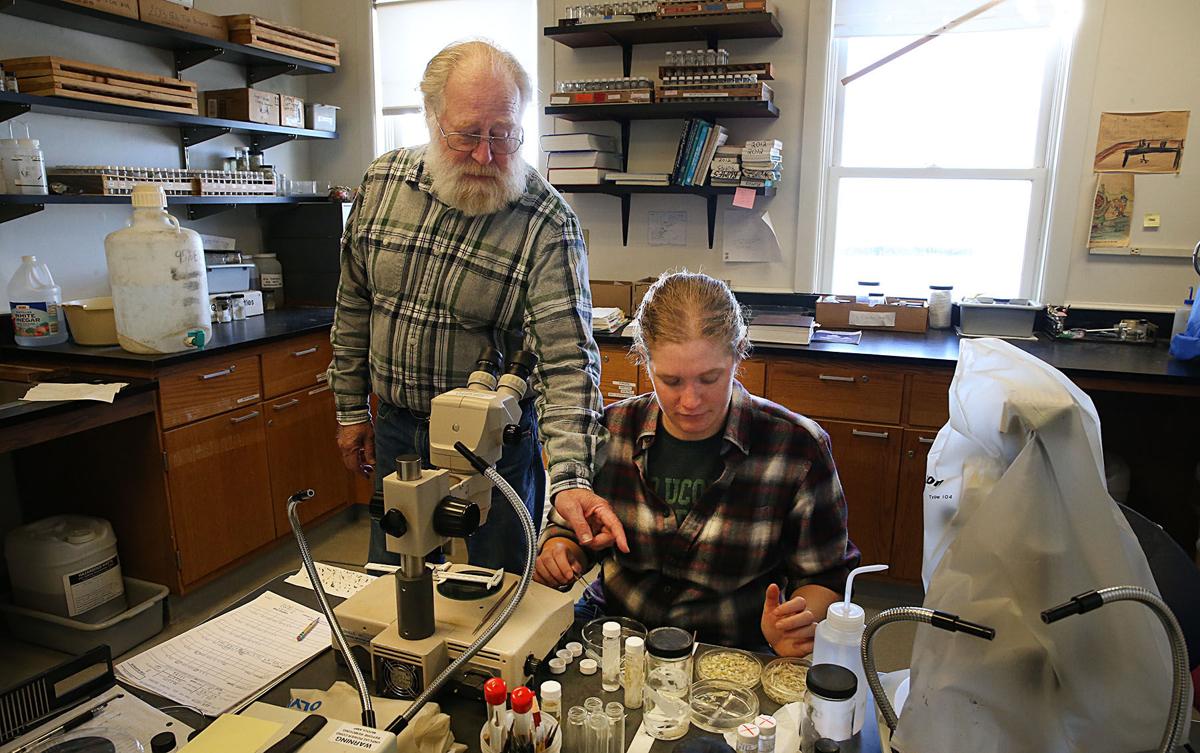

On the first floor, technician Christine Denisevich, of Galloway Township, used small instruments to separate fish larvae samples and examine them under a microscope. The larvae collected from a recent day filled a small jar containing an ethanol preservative mixture.

Some archived jars from past Decembers contain no larvae at all.

“We’ve been looking at change as a concept. The concepts are really simple,” Grothues said. “But what’s different about science is the process of measuring that change. We now have new tools to do that.”

The marine station and the scientists that work there might seem as if they’re isolated on a small stretch of marsh near a small New Jersey town, but their research is far-reaching. Grothues will head to Alaska in April to study salmon runs, using robotic technology.

He was recently featured in a Discovery Channel documentary during Shark Week about the endangered Ninja shark in the Philippines. He previously worked at a marine station on the coast of California.

Paola Lopez, an assistance research professor at the station, works on projects related to detecting pollution in the atmosphere and water. She studies fish otoliths, or earstones, to trace the animal’s history and the habitats it has visited.

Her research is applied to studying fish that migrate from the Gulf of Mexico, where oil spills have damaged the water quality.

It’s an exciting time for marine science, Able said, and researchers in Little Egg Harbor Township get to live as close to marine life as they are allowed, thanks to the U.S. Coast Guard.

“The kinds of things we fish for has changed dramatically over the 125 years of history that are included in the book,” he said. “What we learn here helps in other places around the world.”

Article and Photo Credit: https://www.pressofatlanticcity.com